Dear New MFA Students: Welcome to the Program

Writer’s Note: This post is inspired by the lovely buddy I’ve been paired with who is heading into the first year of the MFA program at The University of King’s College. They are taking my place as the new intrepid student I was a year ago. In talking to them, as I reflected back over my first year, it occurred to me that some of the information I shared may be useful to others, maybe even entertaining…

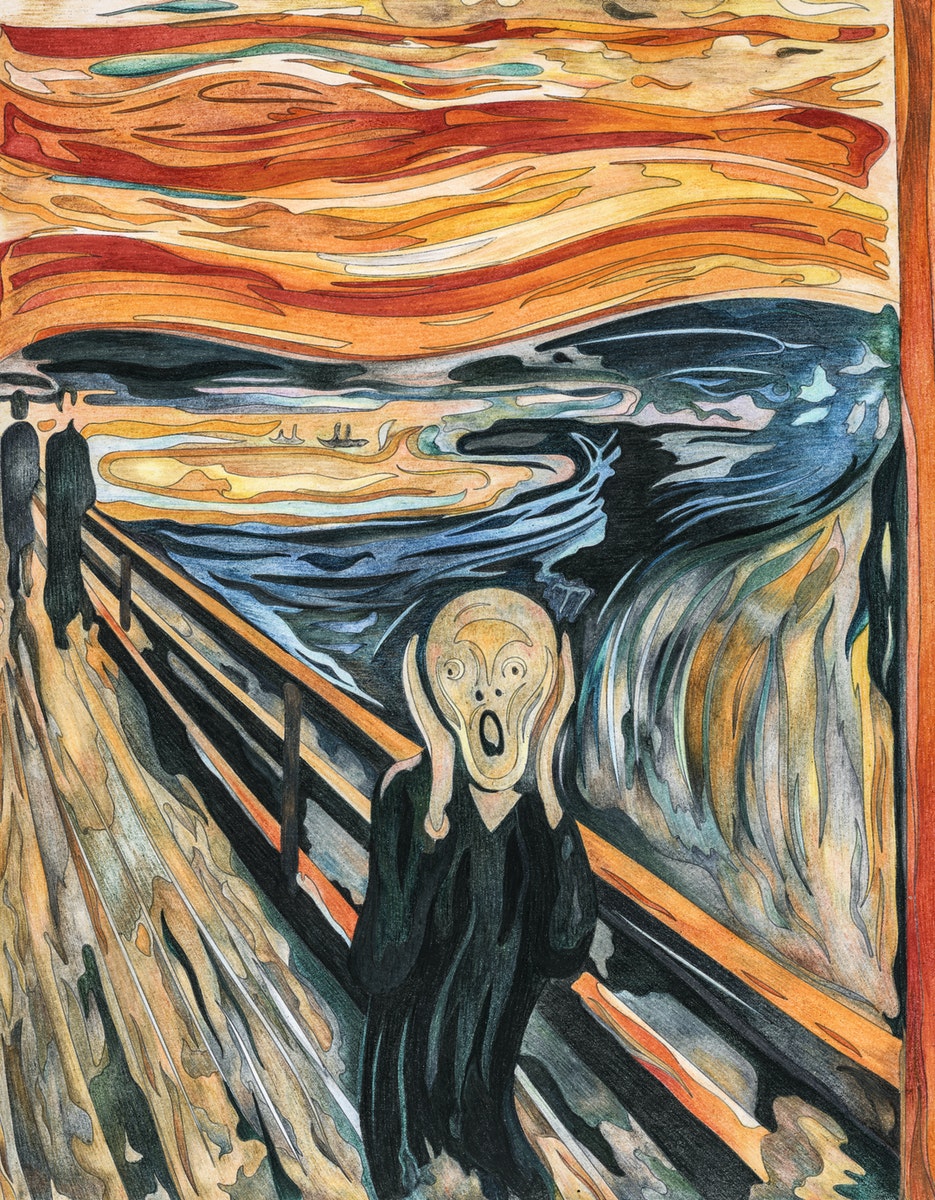

Psst. I’ll tell you a secret. Every student, whether they admit it or not, is encumbered by two universal experiences when entering an MFA program: imposture syndrome and the intimidation factor. Imposture syndrome looks like: I don’t belong here, or—my writing isn’t good enough. The intimidation factor is thinking like everyone will be a better writer than me, because they’ve done ‘x’, which derives from the false notion that your writing isn’t good enough. Hopefully, these thoughts come and go so that you aren’t plagued by self-doubt constantly, but I want to reassure you these feelings are normal. Some encounter them more than others. This is a well-documented phenomenon by writers of all stripes. The angsty voice of doubt whispering nasty thoughts in the writer’s ear, clouding their judgement and creativity. Banish that voice, don’t put up with it, shoo it away. You’re in an MFA program now, and—surprise!—that means you are a professional writer with your own form of talent. You got into the program, didn’t you? You are meant to be here. You have earned it, even—especially—if it doesn’t feel that way. You write and you write well. AT LEAST one other person thinks so. We’ll revisit the intimidation factor in a moment.

You’re here—now what? Get writing! Seriously, the cliché, you have no time to waste, is a thing. If you have research to do, start researching. Books to read, get reading. Pages to write—well of course you have pages to write—start getting those ideas down.

The way the University of King’s College MFA program in creative nonfiction is set up, after the summer residency in June, and a few pesky assignments, you have the summer ahead of you to do with as you will. I want to tell you to relax, enjoy the summer—I really do—and you genuinely should take some down time because the fall term is fast-paced, but hear me out: get ahead this summer. Write enough so that when September comes, you know you already have at least a submission or two prepared. Work enough that some of the assignments are off your plate. Look ahead to the assignments you have coming so that ideas filter through your consciousness. As you read good books throughout the summer, those ideas will eventually have somewhere to land. Take notes. Get organized. Write most days. Then relax. By the end of the second term (first year), many of my classmates and I had run out of gas. The work I put in through the summer got me through to the end. I did not for one second think of devoting my summer to writing as “lost time”, I thought of it as a return on my investment. You are spending an enormous amount of energy and resources to get through this two-year period. The MFA program is a once in a lifetime experience. Best to make the most of it.

But if you do have commitments, such as children, ill or aging relatives to look after, your own health, perhaps it’s full or part-time employment, do what you can, when you can. Every bit helps. I make it sound as though I toiled day in and day out, but my reality that first summer was that I spent a significant amount of time looking after my family. Your reality will demand the same of you. Find the blank spaces and fill the page when you can.

And once you do start writing, don’t stop. You will have to go back, edit, and revise when working with your mentor, but keep looking forward, ahead to the next piece, what’s the next section or essay or scene to lay out? Once you build momentum, keep the momentum going.

Remember: this is not a solo venture. The intimidation factor. Ahh, we have arrived. I mention this because you are now a part of an impressive group. In the MFA program you will encounter seasoned journalists, PhDs, MDs, MBAs, professors, editors, publishers of literary journals; writers who’ve headed up newspapers and magazines, whose writing has won prizes, appeared in The New York Times and who maybe have even published a book or two—or more. Maybe you are one of these writers with professional or academic notoriety—or maybe you’re not. Maybe you’re like me, and coming from a different field entirely, relatively “new” to the writing game compared to classmates with whole careers behind them. Writers’ backgrounds are as diverse as the books they produce. Our lives inform our writing. Have you lived? I’m guessing you have. Nobody else is better suited to tell your story than you, and nobody can tell it the way that you can. That your MFA colleagues come from rich and varied backgrounds full of experience is wonderful news! Learn from these people. You are now colleagues. And give freely of yourself in return.

Psst. Here’s another secret. A little tip from me to you. Pretend like everyone in the program is your friend. You heard me. Just do it. My husband baulks when I tell him this. “Just because you’ve met somebody, Adelle,” he’ll say, “doesn’t mean they’re your friend.” He’s right and wrong. If you adopt this strategy, everyone in the program will not, decidedly, become your best friend. But doesn’t it make for a better world and friendlier atmosphere if you imagine that they will be? And I guarantee you will make a true friend or two—or twenty in the process. Moreover, some of these folks will be your first readers, your work’s biggest champions. These people are your allies. Who better to understand the ups and downs of the writing life? Who better to commiserate with over assignments and deadlines? The pains and pleasures in the pursuit of publication?

It took a short time for me to realize that every writer in the program was a unique talent, otherwise, as mentioned above, they wouldn’t be here. What I’m getting at is that comparing yourself to others is futile. Wasted energy. You can expect and celebrate that you and your classmates will each become successful writers; what that definition of success looks like varies depending on individual goals. As you move through the program together, one writer’s success does not detract from another writer’s success. While this may be stating the obvious, rejection is part of a career in writing, so if you do feel the need to compete, race against yourself and see how many rejections you can collect (like gaining friends through manifestation—you’re bound to gain some acceptances along the way).

Oh! And you will be graded. The grading part feels weird, almost wrong. You’re going to put a mark on my heart work? The two seem at odds. My advice is just to embrace it, again, you are a student, and this part of the process can feel rewarding. When else do you get a grade for doing your work? It’s helpful to remember that if you complete the work on time, the grade range for MFA students runs from above average to outstanding. We are all above average writers. Say it with me. We are all above average writers. See? Doesn’t that feel good. Better yet, forget about the grades and use this incredibly brilliant group of individuals to your advantage: tap into their knowledge and skill sets. Which reminds me.

Becoming a part of the MFA community inevitably exposes you to the larger literary community. Make those connections too, where and when you can. Industry professionals will come talk to you. Their presence and attention are part of the perks you’ve paid for. Follow these writers, publishing professionals, editors, agents and so on on social media if their ideas interest you, or if they are someone you could learn from. Don’t be afraid to reach out to them on an individual basis, after you’ve heard them speak, and make a personal connection if you have a comment or question and feel compelled to do so. Do it even if you don’t feel compelled to do so, but know you should. What do you have to lose?

You are a literary citizen now. What does this mean? It means that you should support your fellow classmates whenever you can. Their successes are your successes. Something as small as a ‘like’ or a ‘follow’ is a boost. Many professional writers dedicate time to promoting, celebrating and actively engaging in other writers’ work from reviews to profiles to interviews and attending book launches. The MFA is a good place to get used to this culture of reciprocity, even when the act of writing can feel so singular—it’s not. We’re sewing from the same fabric of the universe, though each patch has its own sheen.

I recall being fourteen years old and openly mocked for the first time. I was a competitive gymnast, peppy and cheerful. The ponytail wagging kind. It may surprise you to find out that not everybody likes peppy and cheerful. I met a wiry looking girl my age who I later found out had a crush on my boyfriend, which may explain what happened next when I introduced myself.

“Hi! I’m Adelle!” I said in my cheeriest tone, extending my hand in greeting.

She did not, I took note, shake my hand.

Instead, she turned her head and said to the group of girls behind her, “Hi! I’m Adelle,” in a snarky mock tone.

While the girl’s reaction says much more about her issues than it does about mine, I share this story to arrive at a point: nobody is going to openly mock you or your work in the MFA program, I promise. There are rules and guidelines around giving feeding, which will come to your attention. Others will be looking to pinpoint what works in your pieces of writing, rather than what doesn’t, because that is helpful information. They will likely have questions too, and that’s okay. Your mentors, professional editors and writers, will gently guide you toward questions that will strengthen your work. Listen with an open heart and you will not be wounded. You are not your narrator, and constructive criticism will pertain to the work.

I could talk to you about deadlines and word count, but I won’t bother, because Dean is there for that.

Perhaps all of what I’m saying doesn’t fully resonate with you, and that’s okay. You get to make this MFA program your own thing. It’s quite likely that you and I are entirely different people. You may be a brood-in-the-dark-corner-of-the-bar-pontificating-and-pondering-life’s-existential-crises, fist-to-forehead, cigarette-dangling-from-your-lips kind of writer, while I’m more of a friendly-run-with-my-dog-ponytail-wagging-mom-of-three-kale-smoothie-drinking-optimist-who-loves-sunshine-and-trails kind of writer. That’s cool. I’d be happy to sit by your side in the dark for the day and learn from you too.

What matters is that we’ve come together from our various corners of the universe, thread in hand. We’re primed to create something, and this is our moment to shine. Raise your needles. On your marks. Get set. SEW!

I hope our seams will butt up against one another’s. I genuinely can’t wait to see what you will make. I know it will be beautiful.

Enjoyed this post? Consider subscribing to my author newsletter, The Write Page, for writing, reading and retreats that inspire—many thanks! And writers, please let me know about your author newsletters, I’d love to read them. Reach me through my website adellepurdham.ca. Questions & comments welcome.