I’m a sentimentalist, it’s true. I am guilty of romanticizing life at the cottage, both to myself and to others. I tend to focus on the good feelings and not so much on the bad experiences. And there’s merit to this, to being an optimist, to seeing the glass half-full, to finding the positives and looking on the bright side. To letting one’s self get swept up in the moment. But we all know that darkness lurks somewhere in the shadows. I can’t remain clouded to what is difficult and unseemly to write about or I risk only telling half the story – that which is saccharine, sickly sweet. (See Leslie Jamison’s essay, In Defense of Saccharin(e) from The Empathy Exams for a further examination of this topic).

There’s the fairy tale version of our summer stay and the darker elements – the truth of our existence here lies somewhere in between.

Let me tell you a sinister story, reminiscent of brothers Grimm.

Once upon a time there was a princess named Penelope who loved to pick up frogs and toads. All day long, she caught the frogs, watched the toads and cradled them in her hands. At four years old, the little princess was not the best at washing her hands.

Her parents, the king and queen, were very busy running the cottage kingdom, managing three children during a pandemic and working full time. Life in the palace was not always a bed of roses. They argued over responsibilities and often left the children to their own devices. Princess Penelope spent her days down by the shoreline with her frogs.

Now, if this were brothers Grimm, the little princess would likely drown at this point in the story, but stay with me here.

One night, after the royal family hosted visitors for the weekend, the little princess began to vomit. The queen panicked. Was this the dreaded Covid plague? Her poor baby! What had they done! How could they have been so foolish as to allow others to enter the protective bubble of their cottage kingdom?

Mysteriously, the next morning, after having vomited all night, the little princess recovered. She seemed absolutely fine – better than fine. Life returned to normal with princess Penelope catching her frogs down by the shore. The king and queen stopped worrying about the little princess and fell back into their work.

A week later, the vomiting happened again. This time, there had been no visitors. Was this some sort of evil spell? No – poison.

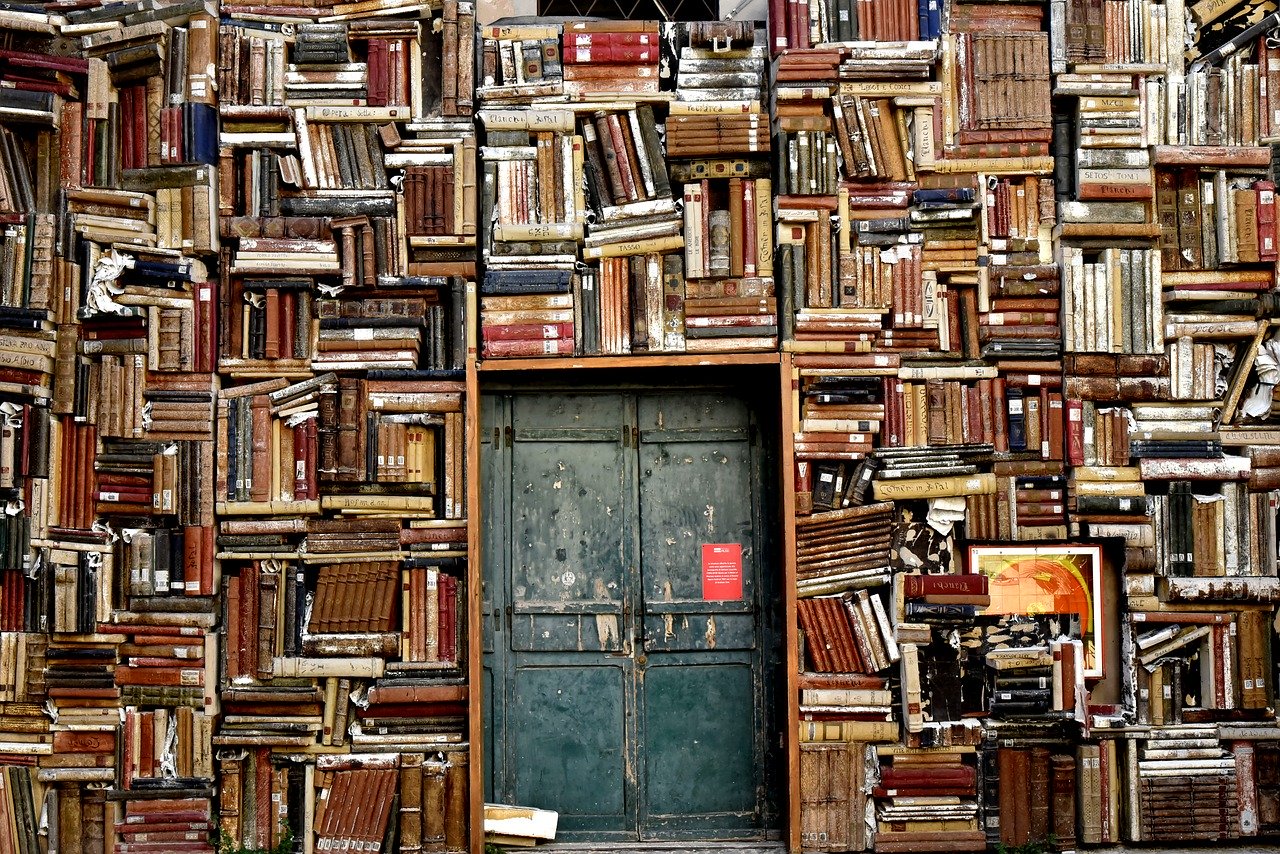

The king happened to remember something he once read in a book of potions about toads excreting toxins.

Little princesses aren’t very good at washing their hands.

Busy monarchs seldom have the time to enforce proper hand washing after every single held toad.

When a toad is squeezed, they excrete a milky poison from their eyes toxic to their enemies. In addition, many water frogs also have bacteria and can carry salmonella, which can lead to some serious intestinal upset. Through further research, the king and queen also discovered that the substance coating certain frogs and toads can be hallucinogenic. So the story of the princess kissing the frog who turned into a prince – who knows? Maybe that’s what she thought she saw, high as a kite.

Furthermore, because a frog’s skin is so porous and takes in its environment so readily, holding it in your hand is akin to having someone hold onto your lung. That cannot feel comfortable, and so, perhaps it is best to leave the frogs and toads be.

Now that the case of the curious night vomiting has been solved, his and her majesty have gently, but firmly, instructed the young princess to limit the number of frogs and toads she holds and to wash her hands after handling every single one. Every single time.

According to latest reports, “I’m holding a toad in my hands!”, not much has changed.

And so this story – and her nausea – may continue unhappily ever after.

But, honestly – what can you do? She’s a kid. Kids are disgusting. And to those who would judge: if you think your kid hand-washes after doing something as dirty as wiping their own ass, check next time, use a magic mirror or whatever you have to do. And when you watch them walk out, hands dry, wipe their nose and pass you by with a grin, maybe then the frog vomiting won’t seem so bad.

Accompanying every bit of life, every piece of beauty, there’s a darker side.

“Oh, I just love the loons!” I told one neighbour,

“Yes, well, they’re not as great as you might think.” The loons eat the native ducks’ eggs, effectively almost abolishing them from our lake. And the ducks that do survive, another neighbour informed me,

“The ducklings – the snapping turtles pull them under by the legs, one by one.” One webbed foot at a time.

Nature is murderous, cruel, relentless, toxic. Leeches that suck your blood, wasps that sting beneath the eye. Toads that poison little princesses like a blood-red apple.

At the end of the summer, I’ll hold a picture in my mind of our sweet four-year in a pink tutu bent over the toad in her hand. All eyelashes and a mop of curls. The remnants of salmonella on her small hands.

I’ll try not to get all sentimental over that picture, over the notion of a tiny girl cuddling with her toads, enjoying her warm summer days, the sparkle of the sun reflected in the water, dazzling, under a bright blue sky, the apple of the frog’s eye. That kind of romanticizing, especially in writing, is enough to make you sick.