What would happen if you followed your dreams?

What would happen if you followed not just your dreams, but that little voice in your head, the one you want to ignore because it completely throws the balance of your life into chaos; that voice with the cord that attaches itself all the way down to your heart. And when that heartstring is pulled, there is no ignoring its song because it’s playing your tune, the tune of who you truly are.

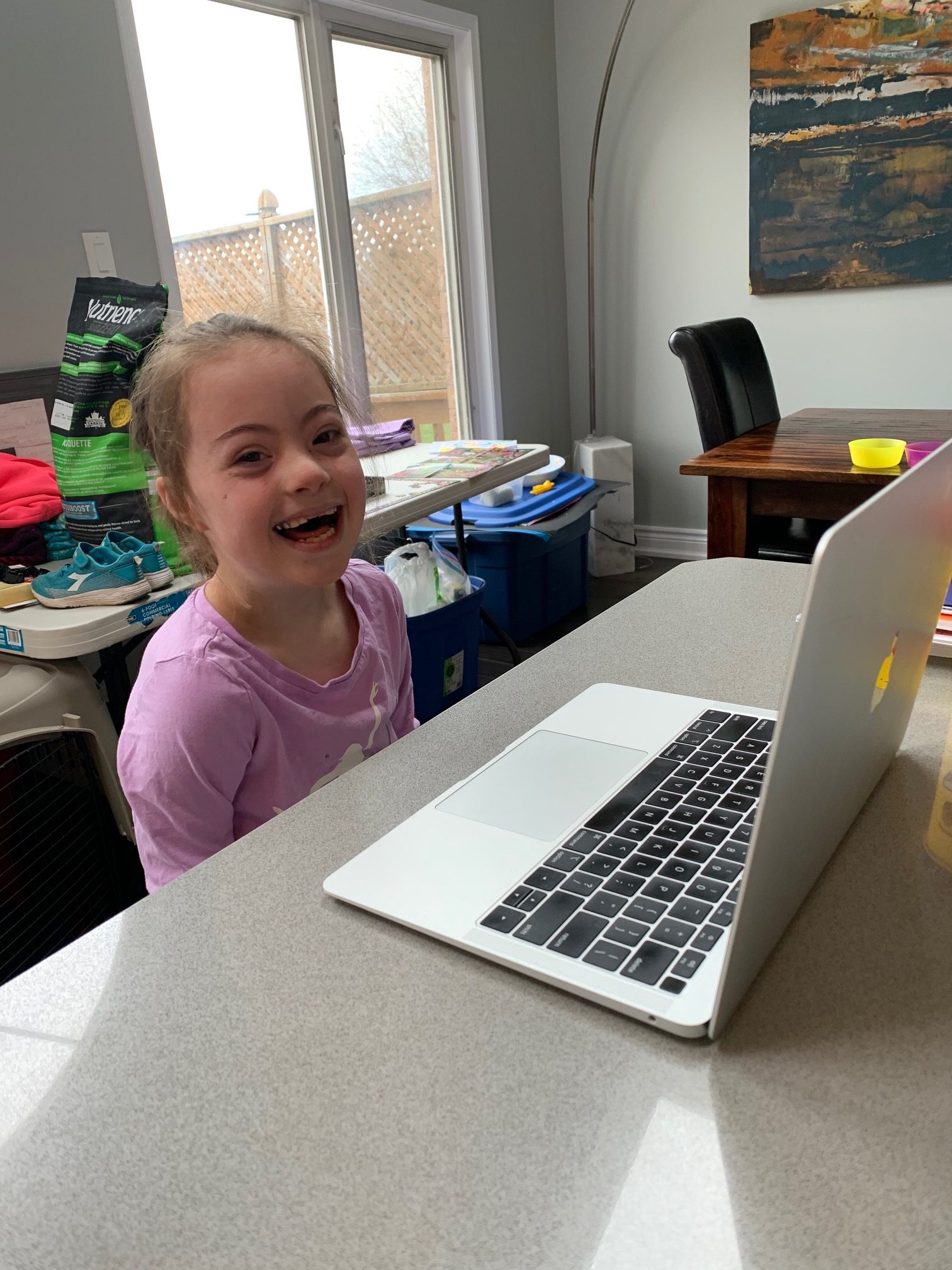

What would happen if your baby was born with Down syndrome and that caused you to question many long-held beliefs that had you standing on shaky ground. Would you then look around at the people standing next to you anew, with a startling clarity? Would you live your life differently, follow a different path? Maybe.

What would happen next? Well, your baby would be born and you would be a mother or father, of course. Personally, I have never really embraced the term ‘special needs mom’, but if that floats your boat, you do you.

You would research the proper use of language to be able to use it correctly with your own child. Was it ‘Down syndrome’ or ‘Down’s syndrome’? A person with Down syndrome (lower case ‘s’) is the correctly spelling and usage in North America, while in the UK, Down’s syndrome spelled with an apostrophe is the norm. You would read and you would learn and, something new – or perhaps, not new, just reimagined – you would write. You would write a blog and one day – today! – you would have been writing that blog for almost nine years, because you started when your first born came along as a way to keep in touch with family far away.

Then what if that blog became something more to you? What if that blog became a story you needed to tell the world? What if you wrote a newspaper article, just one. Just one measly article – what could it hurt? And what if the rush from that one published measly article and your hope to help create a more just society for your daughter would then inspire you to write more, to keep going, to dig deeper, to settle right into advocacy work. And what if then, you joined a board of a local Down syndrome association and you met families, many wonderful families, who have children with Down syndrome, families you may never have been fortunate enough to have met otherwise, but they didn’t really have a regular place to meet – so what if you set that up? What if you coordinated a meeting place and what if you showed up there, who else might you meet? And what other stories would be told? Many. And what if those stories filled your head and some danced for joy and others sank with sorrow into a sea of tears that needed to overflow onto the page? What if you could write about…all of this.

What would happen if you looked for a memoir on the bookstore shelf written by a mother who had a child with Down syndrome…but there were none, well, when you dug deeper, there were a few, but none quite as young or Canadian or as uniquely…you. None with your story to tell. Well then.

What if, scene by scene, chapter by chapter, you began to write your story down. What if your story were to unfold before your very eyes as you devoured books on disability and memoir. What if you read one hundred books a year, for three years in a row, mostly memoir – would you know how to write your own then?

What if you could receive an education by doing, by living, and by reading voraciously? What would happen if you threw in every ounce of emotion you ever felt (leaving room for the emotions of the reader: pro tip), and let it simmer for a while, for a few years and then when you were in the exact right place in your life, which is to say, pregnant and planning to move, which is to say – right in the middle of it – you were to write that book, the story of receiving a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome with your daughter?

And during the process of writing a memoir, what if you were to learn something? About storytelling, and time management, and publication, and copy editing, and narrative arc and plot and weaving in themes and cutting out crap. What if you were to learn something that could be useful to others beyond the obvious of getting that book about Down syndrome out into the word? What if you could find your voice.

What if, in the process of writing your memoir, you dreamed up a whole new career for yourself. What would happen if writing became more than therapy, if it became your lifeblood?

Just what might happen if you decided to take writing seriously? You couldn’t do that, could you. That might be too selfish, play too directly into your deepest desires – or could you? Well, if you keep writing, if you work hard at it, you might just face a whole lot of rejection, and then you might get published in a magazine or two, and you might see more of your name online and in print, and one day, (hopefully soon), you will see your book published, the one that took you three years to write. And by that point you may very well think of yourself as a writer.

You might decide that while writing is writing and writing is everything, that money and making a living is important too. You might become an editor on the side and of course, given your background and inclinations, you might consider furthering your qualifications and continuing your education to better be able to teach writing. You might then consider getting your Master of Fine Arts in creative nonfiction, because you’ve always wanted to do your Masters, you love education, and while you’re waiting to do that, because your children are still growing up, why not travel the world with them? You never know what could happen, so better plan that trip fast. What if your travel agent should tragically pass away, would that thrust you into action? It did for me.

And what would happen, if you decided that you love to write so much you’d like to attend a writer’s retreat? Let me rephrase that with the truth. You want to go to a writer’s retreat so that you can learn how to run your own. Then what would happen if you just went ahead and ran your own writer’s retreat anyway? Would anybody come? Would anybody care? In other words, if you build it, would they come? And would you come into contact with more wonderful writers? Would you have a chance to share new viewpoints and explore the world through the eyes of these dazzling women? You would.

Then what would happen if you wanted to keep your retreat going. If running a writer’s retreat became an important way to connect with others and use your skills as a teacher and a learner and a writer. What would happen if you one day envisioned hosting retreats of your own, in your very own special place?

Then one day, what would happen if the world as you knew it fell apart. If all sense of normalcy was erased. Would you crumple to the floor and refuse to get up? That would be understandable, if that’s where you needed to lie. And some days you do. You lay there motionless, watching the world pass you by.

But what if you held onto hope, and let the heartstring pull and listened hard to your own inner music? Might you remember your retreat, and the second book you are going to write and the MFA program you got accepted into and the people who are counting on you? Even if no one is counting on you, what would happen if you rooted for yourself? Became your own biggest fan? You’re #1 – go me! What would happen if the cheers in your head became louder than all the noise of the outside world? Not in denial, but in defiance and with reverence to all that you are and can be.

What if you thought about buying your family a pool with the money from all the cancelled plans of the summer, but then instead you thought, no, I want to buy a cottage. What if that would cost you everything you had, but would bring you closer to the people you loved? To the nature and the water you worshipped? To following your dreams and dancing to the tune of your heartstring.

Would you listen?

I think I just did.